Moonvalley

Founded Year

2023Stage

Series A | AliveTotal Raised

$154.5MLast Raised

$84M | 7 mos agoMosaic Score The Mosaic Score is an algorithm that measures the overall financial health and market potential of private companies.

+317 points in the past 30 days

About Moonvalley

Moonvalley focuses on deep learning applications in the film and video production industry. Its main offering is a generative video model named Marey, which creates video content based on clean, fully licensed data. Marey aims to assist filmmakers by providing tools for prompt adherence, motion generation, and physics simulation in videos. Moonvalley was formerly known as Contentfly. It was founded in 2023 and is based in Toronto, Canada.

Loading...

ESPs containing Moonvalley

The ESP matrix leverages data and analyst insight to identify and rank leading companies in a given technology landscape.

The generative AI — photo & video tools market provides software that uses machine learning algorithms to automate and enhance image and video creation and editing. Companies in this market offer solutions that automatically generate visual content, enhance image quality, restore details, remove backgrounds, correct colors, and process media significantly faster than traditional methods. These too…

Moonvalley named as Challenger among 15 other companies, including Canva, Synthesia, and Stability AI.

Loading...

Research containing Moonvalley

Get data-driven expert analysis from the CB Insights Intelligence Unit.

CB Insights Intelligence Analysts have mentioned Moonvalley in 3 CB Insights research briefs, most recently on Oct 20, 2025.

Oct 20, 2025 report

Book of Scouting Reports: 2025’s Digital Health 50

May 16, 2025 report

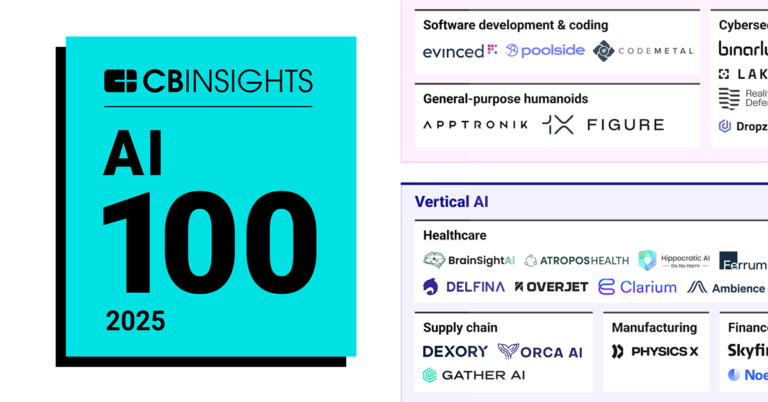

Book of Scouting Reports: 2025’s AI 100

Apr 24, 2025 report

AI 100: The most promising artificial intelligence startups of 2025Expert Collections containing Moonvalley

Expert Collections are analyst-curated lists that highlight the companies you need to know in the most important technology spaces.

Moonvalley is included in 4 Expert Collections, including Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

37,256 items

Companies developing artificial intelligence solutions, including cross-industry applications, industry-specific products, and AI infrastructure solutions.

Generative AI

2,951 items

Companies working on generative AI applications and infrastructure.

AI 100 (2025)

100 items

AI 100 (All Winners 2018-2025)

100 items

Latest Moonvalley News

Oct 22, 2025

Hollywood is having an existential crisis over AI — and a Toronto company is at the heart of it ROB magazine Uncanny valley Generative AI is coming to Hollywood. Toronto-based Moonvalley, which brings together nerds and creatives under one roof, is hoping its ‘clean’ model – trained only on licensed content – will be a blockbuster The Globe and Mail Published 15 minutes ago Bryn Mooser is the CEO of Asteria Film Co., founded last year by Mooser and his partner, the actor and director Natasha Lyonne. Bryn Mooser is the CEO of Asteria Film Co., founded last year by Mooser and his partner, the actor and director Natasha Lyonne. Share Asteria Film Co. is located inside a studio near East Hollywood. The 25,000-square-foot building bears the name Mack Sennett Studios, after the Canadian-born impresario who built it in 1916. Sennett pioneered slapstick for the silent film era—pie-throwing, pratfalls, bumbling police chases—but had trouble adjusting to changing tastes in the sound era. Falling on your keister only had so much appeal when actors could talk. Later in life, Sennett groused that filmmakers didn’t understand comedy. “It’s all well and good to try for gag lines,” he told a newspaper, “but you have to know when not to talk.” When he died in 1960, an obituary described him as “almost a stranger on the Hollywood scene.” Today, this piece of history is home to another major shift in filmmaking. Asteria is one of a handful of studios bringing generative artificial intelligence, which allows entire shots to be conjured from text prompts and images, into professional film productions. “We saw an opportunity,” says Ben Michel, Asteria’s head of creative research and development. “We saw a scary path where this replaces artists altogether, and we saw a path where artists define how it’s used.” Michel wears his hair long and has on tinted glasses and cowboy boots. He once worked in motion capture (“mo cap,” he calls it), where an actor’s movements are painstakingly mapped onto digital creations. His MacBook is open, and he shows me how different the process could be with generative AI. Asteria had filmed an actor skulking around its production space like a chimpanzee. They popped the footage into their software application to render it anew as a chimp gallivanting on the moon, no body sensors or green screen required. The movement of the chimp plodding through lunar dust is, to my eye, identical to those of the actor. The video was made with an AI model built by Toronto-based Moonvalley AI Inc., which purchased Asteria this past December. The company has raised US$154 million, including from Khosla Ventures and General Catalyst, and from the Creative Artists Agency, which represents actors, directors and producers. In July, Moonvalley released its AI model, called Marey, which anyone can use with an online subscription. AI video took off last year when OpenAI released Sora, a text-to-video generator. While it wasn’t the first of its kind, it produced videos that were surprisingly realistic, when they didn’t look like nightmarish acid trips. Sora wasn’t useful for professionals, though, and struggled to render objects consistently and to follow instructions. “You’re guaranteed to lose your mind if you’re going to try to prompt a movie,” says Ed Ulbrich, a visual effects guru and Moonvalley’s head of strategic growth and partnerships. Moonvalley is moving away from text prompts and creating features that mean using AI is less like yanking the handle on a slot machine and more like a tool professionals can wield to get the desired results. For Moonvalley, this is where owning Asteria comes in—the creatives tell the eggheads what they need. Michel demonstrates a camera control feature in Marey: Start with a single frame and draw a path for the camera to follow, and the model creates the rest of the scene. The clip Michel shows me starts with an image of a woman sitting in a car bathed in neon light, which is converted into motion as if someone had moved a real camera around her head. The clip is brief (Marey taps out at five seconds), but Michel says the feature can help with planning or produce a finished shot if, say, filming constraints get in the way. Moonvalley’s competitors, including Google, Runway AI, Luma AI and many others, are doing much the same. One thing the company believes sets it apart is that its model is trained only on content that it has paid for. It hasn’t pillaged the web, as is the industry norm, shortchanging artists and risking litigation. The point is emphasized on a whiteboard in the Asteria studio, where someone has plotted AI video companies on a graph based on “clean” and “dirty” models, and “ethical” and “unethical” approaches. At the farthest reaches of the clean and ethical quadrant is Marey. AI has arrived at a precarious time for Hollywood. Studios are producing fewer theatrical releases than before the pandemic, and box office receipts still haven’t recovered. There are frequent pronouncements that Hollywood is dead. Nobody knows whether AI will hasten or forestall that decline, but what’s not in dispute is that it carries the potential to radically upend how movies and television are made. When writers and actors went on strike in 2023, AI loomed large. The guilds won some guardrails, such as preventing companies from forcing writers to use AI, or creating digital replicas of actors without consent and compensation. Otherwise, the door is (mostly) open. Bryn Mooser’s Hollywood production house, Asteria, is the creative side of Moonvalley’s team. Moonvalley believes studios are ready to walk through. The pitch is that AI offers a chance to work faster and at a lower cost, produce more films and TV shows, and just maybe retain human artistry. The industry will evolve, as it always has. Because who wants to end up like Mack Sennett, right? Audiences haven’t been deluged with generative AI since the strikes ended in 2023. Even the chief negotiator for SAG-AFTRA, the actors’ union, sounds a little surprised. “It’s probably not as widely used yet as we had thought it would be,” says Duncan Crabtree-Ireland. Timing could be a factor—it takes a while to make a feature film. “We do know that multiple groups have got full feature deals, so we should expect some of these things to pop up in the next nine to 12 months,” says Erik Weaver, who is producing an AI-animated short film. Studios are also restrained by a thicket of legal issues. Kent Houston, who runs a VFX company in London, says a major studio he’s working with prevents him from using AI. Even if he could, he’d be hesitant. “We’re exposed,” Houston says. The chance that an AI program spits out a visual that another artist could later claim is substantially similar to their own is making a lot of professionals queasy. Warner Bros., for example, recently sued Midjourney, alleging its AI model was trained on “illegal copies” of its works. Guru Studio, the Toronto animation shop behind Paw Patrol, has used AI to help develop concepts in the planning stage with clients’ permission, but they typically ban use in production. “It’s driven by a surfeit of risk aversion,” says president Frank Falcone. As such, there aren’t many AI-generated pixels in mainstream content. Netflix has said AI tools were used to render a building collapse in an episode of an Argentinian show, while the Amazon series House of David incorporates dozens of AI-generated shots. We only know this because both companies went public with it. The day before Moonvalley released Marey in July, its staff holed up in a windowless conference room at a Toronto hotel, some flying in from Los Angeles and London, to finalize the details. Naeem Talukdar, the company’s 32-year-old co-founder and CEO, didn’t seem nearly stressed enough for someone overseeing a product launch. “A very, very well-known TV show reached out to us recently,” he said, toting his laptop around. Before an episode of this show that he was not at liberty to name was about to air, someone noticed a character wearing the wrong outfit. Reshooting would have cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Outsourcing it to a VFX shop would have taken weeks. At Moonvalley, someone futzing with Marey turned it around in days. “That’s how we envision this stuff,” he says. “You still have the core people.” (The VFX shop no longer getting such patch-up jobs is, presumably, not core.) Talukdar graduated from the industrial engineering program at the University of Toronto in 2015 and co-founded a company called ContentFly three years later with fellow grad John Thomas. It was a marketplace of sorts for freelance writers. Despite scoring backing from Khosla Ventures, Talukdar realized that large language models had become so adept at writing that the technology would eat into his own business. (The irony of AI threatening his first company is not lost on him.) He started winding it down, took a sabbatical and read research papers about AI video generation. He later connected with Mateusz Malinowski and Mik Bińkowski, two Google DeepMind researchers in London who’d worked on its text-to-video generator, Veo 1. Google had been slow to release new products, and the pair was ready to do their own thing. The final piece came when Talukdar connected with Asteria through a mutual investor. The crew (including Thomas and Asteria’s Bryn Mooser) started Moonvalley, raised a US$70-million seed round in November and acquired Asteria a month later. Bessemer Venture Partners backed Moonvalley before it even had a product. “We took a leap of faith,” says Janelle Teng, a partner at the Silicon Valley firm. Bessemer had spoken with at least two dozen AI video companies before investing in Moonvalley, and the company’s plan to build professional-grade tools stood out. So, too, did the market opportunity, which extends into advertising. “There’s a double-digit, if not triple-digit, billion-dollar market opportunity just from two verticals,” she says. If Moonvalley can capture just 1% of the budget of a movie or TV show to start, she continues, then it can build a healthy business model. Bringing Hollywood on board largely falls to Asteria, which was founded last year by Mooser, a producer, and his partner, the actor and director Natasha Lyonne. “Those moments where there can be a dialogue between research and engineering and creative is when you actually push the entire industry forward,” he tells me. Joining Moonvalley made sense in order to bridge those worlds. “It was all just being built by Silicon Valley, and that was never going to fly in Hollywood,” he says. The company is staffing up. Ed Ulbrich, who has spent more than three decades in VFX, including on The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, joined this year. His reason was simple: “Necessity.” A few years ago, he saw viral deepfake videos of Tom Cruise and couldn’t figure out how they were made—he thought George Lucas’s VFX company was responsible. He later joined the company that actually made the videos, Metaphysic, a startup working on aging and de-aging actors’ faces. Ulbrich was stunned at the sophistication. “I can’t un-know what I’m seeing,” he says. He jumped to Moonvalley to work on more than just faces. VFX had also become factory work, rarely affording a chance to interact with directors. AI is different. “It’s an intimate process again,” he says. Moonvalley prefers to position AI not as a means to replace professionals, but as a cost-effective tool to help people make more films. Back at Asteria, Patrick Cederberg sat tucked away at a workstation in a corner. He’s part of a Toronto-based music and filmmaking collective called Shy Kids, and he’d come to learn how AI could help with an animated film he’d been working on for months, during which time he’d assembled about 15 minutes of footage. Specifically, he was learning about low-rank adoption, or LoRA—an AI model fine-tuned on specific material, such as Cederberg’s drawings. He was exploring how to use a LoRA to generate background characters and complete some animation, all in his own style. “It’s less time and energy. It would just be me doing it otherwise,” he said. When I followed up the next month, Cederberg said he wasn’t using LoRAs to produce anything directly for the final film. Instead, the models were a starting point for ideas on backgrounds and character poses. He was also taking advantage of the quirks of AI to create some “demented-looking stuff.” One of Asteria’s flagship projects is Uncanny Valley, a film by Lyonne, Brit Marling and Jaron Lanier, a computer scientist who played a pivotal role in developing VR. The story concerns a teenage girl and an augmented-reality video game, though it’s not clear exactly how Lyonne—who wasn’t available for an interview—is using AI. She told Hollywood Reporter that she’s using actors and a crew, but suggested that AI could help create the video game–like elements of the film. She also emphasized that Moonvalley’s AI model is not “dirty,” like the competition. News of the project sparked accusations that Lyonne was making AI slop. Mooser, who’s constantly asking colleagues about AI, finds some of the criticism puzzling. “When I have young people who are getting their start, who are so strong-headed against AI, I’m like, ‘What system are you fighting for? This could be your shot,’” he says. Even Lyonne couldn’t get funding for Uncanny Valley, according to Moonvalley, but AI helped make the project viable. That’s how the company prefers to position AI: not as a means to replace professionals but to help people make more films. Blockbusters can cost hundreds of millions, while multiplexes in Canada and the U.S. had their worst summer since 1981 (not counting COVID closures), according to The New York Times. If AI can shave some costs, studios might be more willing to green-light projects other than the endless sequels and franchises that have become a reliable crutch. Ángel Manuel Soto, a creative adviser to Asteria who directed the superhero movie Blue Beetle, has been experimenting with Marey. He sees a few potential uses for it, including rendering test footage to see how audiences respond before shooting a completed scene. For Blue Beetle, which cost more than US$100 million, he shot entire fight sequences that were axed. “We’re talking about $1 million or $2 million that you have to throw away,” he says. Replicating drone footage is another option—Soto has already used Marey to create motion out of still images. (He only used the footage to convince the studio to pay for the shot he wanted, however.) He’s not looking to replace anybody, and wants to ensure that both he and his colleagues keep their jobs. To do that, he can’t ignore AI. “If you have all these people hoarding lightsabers,” he says, “I want to learn how to wield that lightsaber so at least I have a fighting chance.” During the Toronto International Film Festival, Amit Jain flew up from the San Francisco Bay Area to spread the gospel of generative AI. Jain co-founded Luma AI in 2021, which is reportedly seeking to raise US$1 billion at a valuation of US$3.2 billion. Jain studied physics and worked at Apple before leaving to pursue Luma, which is pushing its tools deep into Hollywood. “Without AI, studios are dead,” he says. “The economics are shit.” One might expect someone selling AI to say that, but there’s something to it. The director James Cameron said on a podcast this year that to continue making VFX-heavy blockbusters, costs have to be slashed in half, which is why Jain says studios are reaching out to Luma: “Cost is every fucking thing.” In five years, he predicts, every pixel on screen will be touched in some way by AI. Jain pulled out his smartphone to show a montage of clips made with Luma’s tools. In one, a guy in a T-shirt on a patch of suburban grass is swinging a snow brush. Luma rendered the footage into what appeared to be a muscled Highland warrior (or perhaps a Viking) in face paint wielding a battle axe. “You won’t stop shooting movies with a camera,” Jain says, “but why do you have to go to Scotland?” Luma opened an L.A. outpost this fall and hired generative AI filmmaker Verena Puhm to head it up. “We’re here to get everyone passionate about using AI tools,” Puhm says, “and getting rid of that fear.” Previously, she worked as the lead artist on a documentary called Free Leonard Peltier that used AI to recreate events in the life of the Indigenous activist. Jon Finger, another recent hire, shows me a short video in which he pulls a pair of running shoes along the ground by a phone-charging cord. Using Luma, he’d created a car chase out of the same footage, with two speeding vehicles in place of the shoes. The AI model, he says, “just inferred that there should be dust coming off the back of those cars.” Finger isn’t a fan of text prompting. What he’s doing is more like puppeteering, he says. Luma takes the position that training on publicly available data is fair use. When I brought up Moonvalley’s “clean” approach, Puhm started shaking her head. “The studios are talking to everyone, including us,” she said. Building a high-quality video model also requires an immense amount of material; otherwise, it won’t render the world correctly. Even the best ones still aren’t perfect, and the whole industry is struggling to get more data. A few professionals I spoke to had questions about how Moonvalley built its model with a comparatively smaller amount of data. Some speculated it had used another AI model along the way or trained on AI-generated content. Malinowski, Moonvalley’s co-founder and chief scientific officer, shot down those theories. The company, he says, built Marey from scratch. Talukdar adds that they didn’t initially intend to go the clean route because they thought it would be impossible to find enough brokers from which to license videos and images. The first version was lacking in some areas (it hadn’t seen enough animals, for example), so they tracked down more material and did their own due diligence to ensure the brokers had actually paid for it. There are still areas where Marey fails, “embarrassingly,” Malinowski says, when compared to Google’s Veo 3. Marey contained a lot of stock video in its training data, which tends to have a slow-motion feel. “A few months ago, it was a bigger problem,” he says. “I would say it was behind in some categories. But in some, it’s looking better than Veo 3.” Malinowski declines to name the data brokers Moonvalley used, however, and Marey remains a bit of a black box. He did say that it’s considering hiring a firm to audit its data, which could provide more clarity. Jain, Luma’s CEO, doesn’t have any kind words for licensed-content-only models. “They’re doing a grave disservice to creatives,” he says. Training on a restricted set of data impairs quality, he argues. “If you want to build intelligence, you need to see the universe.” Talukdar doesn’t entirely disagree, though he says Moonvalley is talking to studios about fine-tuning its model on their proprietary content, so that it can be tailored for their needs. Mooser contends this will be the industry norm. “We see a world where everything being made has a custom model with it,” he says. (Runway announced this kind of deal with Lionsgate last year.) But with studios already using AI, Moonvalley’s rigorous adherence to licensed data might not be the deciding factor. Amazon’s House of David, for example, used Runway. “It seems to matter less, candidly, than I thought it did,” Talukdar says. The legal uncertainty could also resolve in favour of AI companies, with courts or governments deciding that training on internet data without compensation amounts to fair use. Mooser seems unbothered, saying that studios and union guilds will determine their own standards, regardless of the legal outcome. “We feel quite strongly that having something that’s trained in a way that is responsible and commercially safe is worth doing and fighting for,” he says. The Asteria team has serious Hollywood cred: These two Emmys belong to Mooser, and his partner, the actor and director Natasha Lyonne, has a few of her own. Talking about generative AI in Hollywood is still sensitive. A couple of executives at notable production companies would only talk if I didn’t use their names. Both were figuring out how, when and if to use AI. “You could do it solely for cost purposes, but I’m not so sure that’s what everyone wants,” one said. “Quicker and easier is one piece of it. But also, is it cooler?” The other said his company would use it if filmmakers could pull off something that couldn’t be done otherwise. He doubts the public will ultimately care about the use of AI, at least not enough to hurt the bottom line. It’s not just producers grappling with AI; everyone is, perhaps none more so than VFX artists. They can use these tools (Talukdar says VFX shops are becoming customers), but AI could replace some of the work they do. “We did not appreciate how dramatic the developments would be,” says Matt Panousis, co-founder of Monsters Aliens Robots Zombies Inc., which began as a VFX shop in Toronto and has incorporated AI for years. Its main product today is AI-powered lip dubbing for foreign languages. It has taken off because there’s a huge market beyond film and TV, and Panousis prefers to market the company as LipDub AI. It still does some VFX servicing work, but there could be tough times ahead. “It would have taken a team of artists months and months to get a shot,” he says. With AI, “that’s a keystroke.” Some VFX pros are skeptical. What AI developers might not understand is how anal directors can be. Mark Weingartner, a VFX director of photography and VFX supervisor in L.A., says some are maniacal about the smallest details, like how a piece of debris rotates during an explosion. “I’ve watched this happen where a director or visual effects supervisor will absolutely fixate on something, and a huge amount of resources can go into 12 frames,” he said. AI, in his view, doesn’t yet offer that level of control. Some of the tools AI companies are offering, like Moonvalley’s motion capture alternative, could be helpful as a first step for some jobs, says Adrian Bobb, a former VFX pro in Toronto turned director. But getting to a finished shot entails churning through multiple drafts, and Bobb wasn’t convinced AI was reliable enough yet in terms of time and cost. In meetings, he says, someone inevitably asks, “Can’t we just do this with AI?” He advises that other methods can yield better results. “You either have money, time or quality, but you can’t have all three,” he says. AI may prove to be just one more tool among many. If you look closely at the sizzle reels AI companies have put out, you’ll still find some weird stuff—airplanes defying physics, a mermaid flapping her tail and leaving no ripples. “It’s not a production-ready technology,” says Jake Aust, chief innovation officer at AGBO, the studio behind Avengers: Infinity War. He wonders how much benefit AI really had for the Netflix and Amazon productions, and suggested optics are at play. “There’s a rush to be able to say, ‘I’m doing it.’” Some professionals feel that refusing to work with AI will close doors. “If you don’t learn it, you’ll be left behind,” says Roberto Schaefer, a cinematographer whose credits include Finding Neverland and Quantum of Solace. He recently worked on an animated short that included a crew of artists using a variety of AI models, even refining prompts with ChatGPT. Schaefer bounced between them to discuss lighting, framing and camera movements—all things he would do on any other film, but without a camera. Artistically, he said the process was basically the same, “just being done by other hands than mine.” Filmmaker Justine Bateman, who once said generative AI was one of the worst things society had invented, met with OpenAI a couple of years ago and told them the industry’s biggest problems have to do with distribution and marketing. AI does nothing to help with that. If it kicks off a wave of new content, it could make the problems even worse. “You put together a whole film and use generative AI,” she says. “How do you get people to watch it?” She wants to see a flood of AI-generated content because she’s convinced audiences will tire of it, and crave something raw and human again. “On the other side,” she says, “it will be wonderful.” Progress certainly isn’t slowing down. Moonvalley, for one, is working to improve the resolution of its videos, making it easier to get AI-generated pixels on screen. (Today, there’s an entire upscaling process to get to film and TV standards.) OpenAI, meanwhile, is backing an AI-generated animated film. Amit Jain says Luma’s tools are being used on an AI-made feature, too, only this one will be akin to live action. Before I leave the Asteria studio, Mooser gives me a tour. In the lobby is a model of the building as it existed in 1916. “It was built with no roof. There was just sunlight, no electricity,” Mooser says. There’s a bar in the basement, named after silent film star Mable Normand, where Asteria now throws events and parties. We pass through the cavernous studio, where Mooser pulls back a curtain to reveal a glimpse of a towering matte painting that once served as a backdrop for a long-forgotten production. “Beautiful,” he says absently, before dropping the curtain. Sometimes we honour the past. Other times, we have to move on.

Moonvalley Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

When was Moonvalley founded?

Moonvalley was founded in 2023.

Where is Moonvalley's headquarters?

Moonvalley's headquarters is located at 1050 King Street West, Toronto.

What is Moonvalley's latest funding round?

Moonvalley's latest funding round is Series A.

How much did Moonvalley raise?

Moonvalley raised a total of $154.5M.

Who are the investors of Moonvalley?

Investors of Moonvalley include General Catalyst, Khosla Ventures, Y Combinator, Comcast Ventures, Creative Artists Agency and 10 more.

Who are Moonvalley's competitors?

Competitors of Moonvalley include Synthesia, Runway, Stability AI, Metaphysic, Pika and 7 more.

Loading...

Compare Moonvalley to Competitors

Alpaca focuses on the intersection of artificial intelligence and art and operates within the technology and creative industries. The company offers a suite of AI tools designed to assist artists in their creative process, enabling them to generate images, refine concepts, and experiment with style and composition. Alpaca primarily serves the creative industry, particularly artists and designers. It is based in Montreal, Canada.

Runway focuses on advancing the fields of art, entertainment, and human creativity through artificial intelligence. The company offers tools that enable the creation of visual and multimedia content, leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) to provide users with control over stylistic elements in their projects. Runway primarily serves the creative industries, providing solutions for filmmakers, artists, and storytellers. It was founded in 2018 and is based in Dover, Delaware.

Pika is an idea-to-video platform that transforms creativity into motion across various domains. The platform offers text-to-video conversion, image-to-video transformation, and video-to-video modification, enabling users to create dynamic video content from various inputs. Pika provides tools for creative control, including video editing, lip sync technology, and sound effects generation, to enhance user-generated content. Pika was formerly known as Mellis Labs. It was founded in 2023 and is based in Palo Alto, California.

Higgsfield involves in cinematic video generation with a focus on dynamic motion control within the video production industry. The company provides camera control tools that enable creators to generate various cinematic movements, including 360 Orbits, Action Runs, and Bullet Time. Its tools aim to provide preset motion controls that can be applied to video projects. It was founded in 2023 and is based in San Francisco, California.

Neural Love is a company that focuses on artificial intelligence tools for creators and businesses across various sectors. The company's offerings include image generation and enhancement tools, as well as a collection of public domain images. It was founded in 2020 and is based in Harju maakond, Estonia.

DeepBrain AI focuses on artificial intelligence and operates within the media and technology sectors. The company provides tools for video content creation, including a video generator that uses AI avatars and voiceovers in multiple languages, as well as features for dubbing, text-to-speech, and deepfake detection. DeepBrain AI's solutions are used in industries including digital education, marketing, broadcasting, and customer service. It was founded in 2016 and is based in Seoul, South Korea.

Loading...